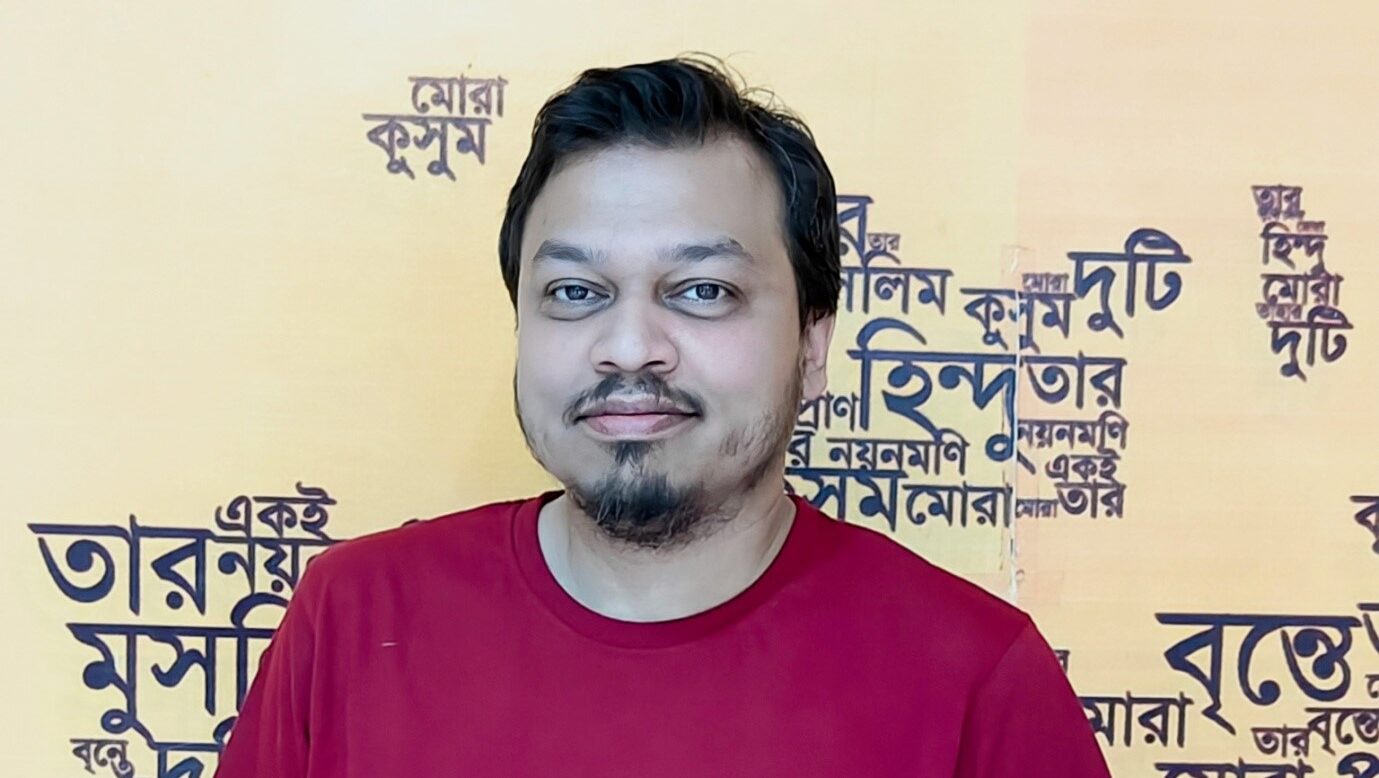

Author and artist Ratul Chakraborty holds in his hand and heart the love of a civilisation that has in balance everything that is meaningful, profound and sustainable. It is fortunate that he has decided to dedicate his time fully to the documenting of all that is precious about Bharat, quitting his extremely successful job as a video game designer. Through his writing, his pictures and his thoughts we get a glimpse of how he is going about his own exploration of this ancient culture, but also through his modern sensibilities sharing it with his audiences to much acclaim.

What was your childhood like for you to have such diverse interests as gaming and Indian cultural history?

I come from a typical middle class ‘Bangaal’ (that’s the word we Bengalis use for those of us who are originally from present day Bangladesh) family. Our family got uprooted by jehadis back during the partition days and lost almost everything they possessed. My grandparents underwent unimaginable hardships as they worked tirelessly to rebuild their lives from scratch as well as support our extended family. Of course, being really old school, they hardly ever spoke about those days, especially in front of me. I came to know about our background once I grew up a bit- mainly from my parents.

My love for stories comes from my grandmother. As a kid, every night before I went to sleep, I would pester her to tell me a new one. This was my magical gateway to the world of folktales and itihasa– which morphed into an insatiable appetite for reading as I grew up. My favourite time of the year was the Kolkata Book Fair; I would scrounge and save up every bit of pocket money for months preceding the event so that I could splurge on books!

My love for gaming began when I first used a pc at my friend’s place- I remember playing a 2D side scrolling martial arts game called ‘Karateka’ and being absolutely blown away. I got my own pc around three years later, and my great love for the medium of video games truly begun as I applied my programming skills to make small games or modify existing ones. Even at that age, I knew this was what I wanted to do in life!

Are the two exclusive in the kind of creativity involved, which made you leave the world of video gaming at your age and take up writing full time? Can we see an interplay of game design and emotion in your future work?

I believe any high-quality creative process involves an intense period of churn- an intellectual Manthan so as to speak, which allows us to finally reach clarity. This churn is both internal to the creative mind as well as a best practice for top level teams regardless of industry and discipline. Ultimately, a big part of the satisfaction from what we term today as the “Creative Process” comes from our participation in this Manthan and the insights we gain during and after the process. In that regard, both video game making as well as writing are supremely satisfying from a creative perspective.

Secondly, there are certain creative concepts which can be very effectively applied in both fields. For example, I adapted the well-known Hero’s Journey narrative structure to the field of game design to define gameplay and player progression systems. The same goes for applying concepts like Rasa theory- in the end it boils down to finding a way to generate certain emotions within the reader or player!

However, there are essential differences- video games are an interactive medium first and foremost, which are built by multi-disciplinary teams of specialists. The dynamics of creation are totally unique- highly dependent on data points, business models, evolving tech, market flux, team capacity etc. On the other hand, writing a book is a lot more personal- the final manuscript (regardless of its sales) is a true reflection of your own creative capacity and mastery of the craft of writing- there is no place to hide!

In my case, I am still someone who loves to play video games- the decision to move on from game making is as much about exploring myself as anything else. I myself do not know my own destination, and my only hope is that I am as true to myself as possible on this journey, no matter the shores it takes me to.

Do you like the short story format? How long did it take for you to write your first collection of stories, Sutradhar? Were the ideas from your experiences or reading or both?

I began this journey not as an author, but as a storyteller. Each of the stories in the book started out flashes of inspiration that I had quickly jotted down. In true bardic tradition, I began to expand and embellish these at every retelling, and soon the scribbles began to resemble stories! When I thought of writing Sutradhar, I was clear from the very beginning that it was not going to be a straight retelling of historical incidents. My target was to create dramatic original content set in specific historical periods. So, I decided to use these existing notes as a base for the book.

Coming from a video game background, I looked at each of these stories as a self-contained prototype, which can then be transferred individually or collectively to other media platforms and formats also. Another consideration was purely practical – I was not getting enough time at a stretch to write, and felt that I could tackle smaller stories more easily than attempting a full-length novel.

The process of writing Sutradhar was the most challenging yet fulfilling episode of my life. I had been writing Sutradhar in snatches for the best part of a decade, suffering through year-long writer’s blocks and periodic loss of inspiration. There were often times where I felt that it was a futile, never-ending pursuit. But then I would read something or see something on social media that would cause an emotional upheaval, and I would write furiously for a week or so before reverting to my daily grind. I committed so many of the basic mistakes that writing coaches warn against – not making writing a habit, endlessly rewriting the same sentences, not having any idea where the plot was going most of the time… all of it guaranteed to make one lose his mind in frustration.

However, the book had taken on a life of its own – it kept gnawing at the back of my mind until I decided to take a break from my job, and committed myself 100% to finishing it. I vowed not to pick up a video game controller until I got to the end of the line, and after two months, I had the first draft of the manuscript in my hands! The joy at that moment was indescribable – I began to message friends and family with the widest smile I remember having since my marriage. That moment of joy sustained me through the multiple cycles of rewrites that I went through, which otherwise would have felt very painful indeed.

Structurally, each story in Sutradhar has three layers – the events in the story itself, the grand theme that underpins those events, and finally what I call the Bharatvarsha layer – the intangible quality which infuses the very being of our Rashtra that I hope to have succeeded in presenting to my readers.

It has been my good fortune to draw inspiration from a plethora of sources, from the books that I have read to the games that I have played to obscure nuggets of information found while trawling on the web. I still get goosebumps when I recall Abanindranath Thakur’s evocative portrayal of Bappa Rawal’s adventures in one of the chapters of Raj Kahini- the first book I really fell in love with as a kid. I started to write from a young age itself, and still remember the joy when my first story got published in our school magazine – and that story incidentally holds the kernel to the final story of Sutradhar, The Path of a Coward! As I grew up, my cultural horizons also expanded – from Japanese Manga like Buddha and Lone Wolf and Cub, to Russian literature like Dead Souls and The Greatcoat, to the great Indian works of Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Sharadindu Bandopadhyay and Kalki Krishnamurthy.

In the Ramayana, Valmiki says there is a Dharma of the Writer. One has to write only what is true. In a creative work weaving myth and history, what is the civilisational truth that you seek to convey? As you embark into a full-time writing career, what future do you see for fiction writers from India who value a Sanatana Dharma history?

In my opinion, the fundamental truth about our civilization is that we are a tribe of seekers.The pursuit of truth through our Sadhana is the essence of the Hindu way of life.

The barrier to this Sadhana in the Kaliyuga is Maya- the fundamental untruth that casts an illusion on everything that we come across, distorting our perception of reality itself. This distorted understanding of reality then manifests as Tamas which shrouds both the society and the individual, making us inert and unresponsive- dead before death. Therefore, I believe that the greatest threat to Hindu civilization is the Maya which stops us from the pursuit of truth.

The question then becomes, how does Maya operate? For me,it is first and foremost a social disease that hijacks our mind and infects every institution in order to stop them from performing the common good, if not acting against it outright. There are three broad layers in which this happens- education, entertainment and information. These three form the virtuous triangle that supports any civil society. The ability to hijack and distort these institutions means having the power to mentally dominate the entire population.

Education is how we pass on the right values and ethics to our next generation. Entertainment is how we tell stories that imprint those values in the social fabric of a civilization in the form of culture. Information is how we see those values succeed in real time, and learn from the instances when it doesn’t. Now what happens when we don’t pass on the right values? When our stories don’t celebrate who we are? When the right information is hidden away from us? We become ignorant- knowing neither the world, nor ourselves. The result? A spineless, self-loathing, deracinated generation, ripe for manipulation and slavery, living in an Adharmik society where MatsyaNyaya– The Law of the Fish, reigns supreme.

This is the challenge in front of any author (or broadly, creator). Our dharma is to be fearless in the pursuit of truth, and hammer away at the mental shackles of Maya that continues to colonise our minds collectively and individually. The seeker necessarily pursues the truth alone, submerged in his lonely Sadhana- but shattering the walls of illusion to unlock the path to truth can and must be a collective social project, like building the Rama Setu.

However, just like the Rama Setu episode, it is not enough to tame the sea. As authors it is our duty and responsibility to explore all facets of the Srishti, Sthiti and Pralaya cycle which is the beating heart of all aspects of creation. It is not enough to demolish the distortion and untruth of Maya; without an uplifting and aspirational alternative vision all it would lead to is cynicism and confusion. Thus, we all must become bards singing the raag of the “Great Bharatiya Dream”, and use our craft and skills to share that glorious vision to all our readers.

In the end, I echo the sentiment of the unknown Karsevak– I aspire nothing more than to be a monkey of the vaanar sena.

You mention in a tweet that you are listening to Beethoven’s 9th Symphony through a Cayin RU7 powering an Audeze LCD X. Technology has changed our experience of music. Would you say the same with reading and writing?

Technology is the interface through which we access the world; it is not just music, not just reading, not just writing- each and every experience of the human condition is coloured by the technological zeitgeist. Just like every other aspectof our universe, the technological space evolves with its own momentum. That does not mean that the evolution is good or bad, but that it evolves and will continue to evolve whether we like it or not. In the same vein, the flipside to technological evolution is technological extinction aka obsolescence.

What we are seeing today is this evolution/extinction cycle is happening at an unprecedented speed never before seen in human history. The trap here is if we focus too much on the technology, then we lose sight of the fundamental- the experiences that matter to us. This leads to a sense of constant dissatisfaction, as the market continues to evolve and we are bombarded with advertisements about how the “new” product is so much better than last year’s version. This is of course by design, since a consumer market driven society is dependent upon constant purchases from the population to maintain the unstable equilibrium between economic growth, inflation and employment.

I remember an interesting incident- someone had asked me for a recommendation for buying a new headphone. I had told him that his current pair was decent enough, instead he should figure out a way to find more time to actually listen to music. That was definitely not the answer he was looking for though, for the subconscious objective was not the experience of listening to music, but the chase of a dopamine high from the feeling of power when you pay for and acquire a new gadget. My own perspective has always been to centre myself around the experience, and then use technology to streamline it. For example, I absolutely adore the Kindle, because it allows me to read anywhere in the most comfortable way possible- like in a dark room at night!

Animals are a very important aspect of Indian writing and culture. In the modern world, the urban human doesn’t connect much to them. Except those who have pets. Is there something we are missing when we ignore the animal world?

The concept of interconnectedness of life is one of my most cherished learnings from Hindu dharma. My story “A Mirror for the Ants” from Sutradhar is essentially based around this fundamental truth. The more I read, the more I realize the sheer magnificence of the intricate civilizational design that unified ALL life, seen and unseen, into the lattice we call Bharat Varsha. If we open the map of Akhand Bharat, and superimpose all the Shaktipeethas and Jyotirlingas and the Dhams and the Teerthas on it, the sacred design will become clear to us instantly. Each region is its own ecological entity, governed by the presiding deity and guarded by a kshetrapal, following the rhythms of the ritual calendar which mirrored the natural one, striving to maintain balance between economic activity and regeneration of natural resources- all of them connected by threads of Dharma and sacred pathways for Yatras that created the cultural unity that survives in some form even today after thousand years of barbaric assaults. This is a glorious vision, though one which is completely at odds with our current reality where we chase the chimera of eternal growth while paying lip service to sustainability.

In fact, I would say that the difference between animal world and human world is an artificial one from a Hindu perspective- for us, we either live in a world where all life flourishes in harmony, or we live in a world bereft of balance. The greatest example of this is possibly the Ramayana- even when Shri Rama is living in the jungle, he is threatened not by the wild animals, but by Rakhshasas hell bent on bringing disorder and chaos. Ultimately, it is with the help of the non-humans that Shri Rama is able to rescue Ma Sita and defeat Ravana, and restore harmony in the world, heralding the golden age we call Rama Rajya. Is there any other culture that expresses such a glorious and profound commitment to the interdependency of life? As one of my favourite verses from the Upanishads go,

ईशावास्यमिदंसर्वंयत्किञ्चजगत्यांजगत्।

Your stories have a connection with places. You have taken pictures on the go… how do you capture stories through your frames?

I love photography because it touches three things I absolutely love- exploring the technology of the camera/lenses, mastering the technique of capturing different types of shots and most importantly, finding stories worth telling. Today we live in a world where photographs, by their ubiquity, have become a part of collective cultural lacunae- vast amounts of data that are so transient that they barely register on our minds as we scroll past them on our tiny screens. As a creator, you want your work to reach as many people as possible- but what does reach actually mean in today’s indifferent world? Does it mean the algorithm puts your image in the maximum number of scrolling screens as possible? Does it mean likes and shares? Does it mean that only a handful of people who really care see it? The question boils down to that torturous consideration- what’s the point of doing all this?

It feels amazing to imagine that I am able to take a photograph so powerful that it will make someone stop scrolling. But that is neither something one can plan for, nor is it something that makes me lug around a heavy camera kit on the streets. No. My purpose is entirely a lot more… selfish. Photography for me is an extremely personal activity. It is something which makes me feel like an explorer, a scientist and an author at the same time. Looking at a scene, thinking of a shot, looking at a face and KNOWING that I NEED to capture a portrait- these are the things that matter. That is why I do it. The process and the experience which leads to the final picture – in the end, in my opinion that’s where one can find lasting satisfaction.

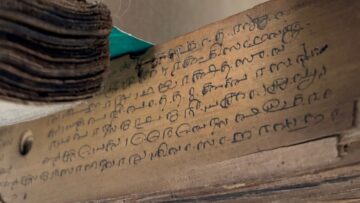

Every Hindu ritual begins with a Sankalpa mantra. This mantra can be considered to be the earliest example of what we today call “MetaData”- data about data. Open any photo on your phone, and you will see that it contains the date, time and place where it was taken, the camera settings you used and the details of the file format itself. This is actually independent of the contents of the photograph, which are unique in every case. The Sankalpa too contains data about data- who is doing the ritual, for what, when and where. I literally got goosebumps when I first heard and understood the phrase “जम्बुद्वीपेभारतवर्षेभरतखण्डेआर्यावन्तार्गतब्रह्मावर्तेकदेशेपुण्यप्रदेशे…” While I marvelled at the genius of our ancestors, I asked myself why? Why did the ancients take such efforts to pinpoint a subject, a place and a time with such fidelity?

The answer, in my opinion, lies in the foundation of culture. A civilization does not grow in a vacuum- it takes on specific characteristics based on its geography, climate, history and demography. This is the diversity that acts as the Darwinian force that has allowed mankind to spread across the planet in a kaleidoscope of cultures. Yet man is man. The great Japanese auteur Akira Kurosawa once remarked,

“Human beings share the same common problems. A film can only be understood if it depicts these properly.”

Even though the context might be different, human emotions are universal. It is with these emotions that we connect when we read, watch or play something. Thus, we can consider diversity (place/time) and universal emotions (through characters we start to care about) as two halves of the creative base that makes everything else from plot twists to dialogs click in the reader’s mind; one can almost call it Realness! This feeling is what I personally try to capture whether writing or game making- Universal Emotions in Local Contexts.

Let me end with an example- a few years ago my wife and I went to visit Orccha (in MP). By sheer luck the day we arrived was the marriage ceremony of “Ram Raja Sarkar”- the locals told me we were immensely blessed to have arrived on such a day. In the evening both of us participated in an elaborate wedding procession to the Janki Ma temple- an experience of a lifetime which I will never forget. I got to know the historical background of this event, and realised that now we too were a part of that continuum. An intensely local custom, fused with the universal emotion of Ram Bhakti, a common activity of tourism and the personal story of a couple getting a lucky surprise- all of them combined to make it a unique story that I never tire of telling!

It is true what they say- the magic of our great civilization is a living, breathing entity- we only need to open up our minds to see its wonders.