A very ancient Shanti Mantra taken from the Krishna Yajurveda Taittiriya Upanishad (2.2.2) is usually recited in prayer before the start of the classes in schools across India today.

ॐ सह नाववतु।

सह नौ भुनक्तु।

सह वीर्यं करवावहै।

तेजस्वि नावधीतमस्तु

मा विद्विषावहै।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Both the students and teachers are together requesting Parabrahman for protection. They are both further asking together for the experience or delight for the nectar of their study. They appeal to the Supreme Parabrahman that together, with joyful interest, enthusiasm and courage, they put together tremendous effort, exercise their mental muscles, view the subject matter from different perspectives. They urge that may they together realize the brilliance from this study. And in the process never be in conflict.

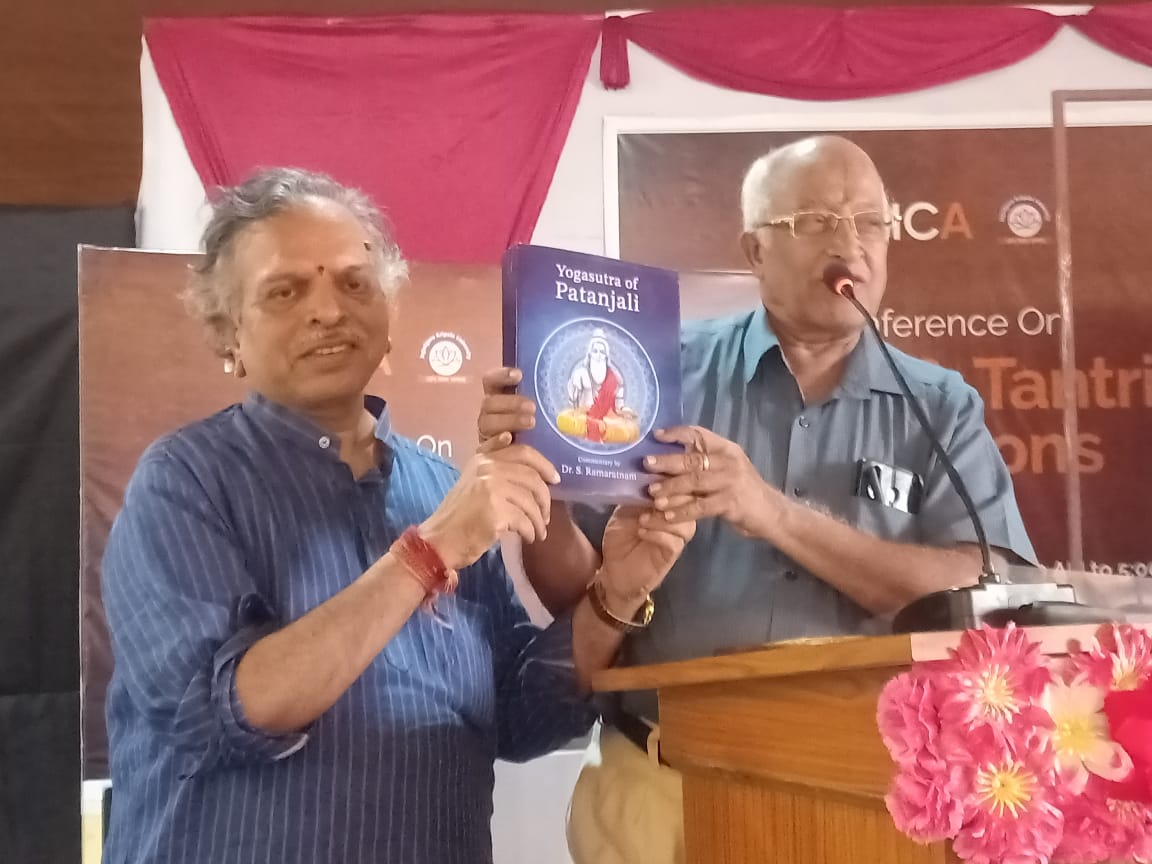

INDICA organized a conference on Bharat’s ancient and time-tested pedagogy, which has contributed to her rich educational heritage between October 27 to 29, 2023, in the historic city of Ujjain. The conference was curated by Dr Nagaraj Paturi and Smt Sahana Singh. Dr Bhagwatilal Rajpurohit, Ex Director of Vikramaditya Shodhpeeth, gave the inaugural address on Ujjain’s Cultural an Educational Heritage.

Speaking on the role of Education in Ancient India, Smt Sahana Singh, an expert on the subject, says, “Education was considered the foremost duty of every individual. Chanakya said that a person without knowledge would not be respected despite having beauty, youth and good lineage. He compared such people to a beautiful Kinshuka flower having no fragrance. A distinction was made between lower and higher knowledge. Practically all that we study in schools and colleges today – geography, physics, chemistry and so on would have been categorized as lower knowledge in the past, even though essential for development. Atma-jnana was considered to be the highest knowledge and therefore every stream of lower knowledge was to be oriented towards ultimately upgrading to the seeking of higher knowledge or an understanding of higher consciousness. As students proceeded in their education, they also learned the importance of the society which supported them and how they too needed to support the samaj in various ways – by boosting their morale via discourses and guiding them towards noble actions.”

Her book Revisiting the Educational Heritage of India is now on the curriculum of many institutions across India. Asked how the conference takes her research further, Smt Sahana says, “The conference was designed by intent to go deeper into the subject matter of my book on India’s educational heritage and to lead to research in the different pedagogies used to study various disciplines such as sciences, fine arts, performing arts, mathematics, music and so on. For example, it invited scholars to probe into how stories and games were used to teach various subjects by actually looking at Shastric references. It was challenging because most modern scholars have generic ideas about ancient pedagogies but have not really gone deep into Shastras or living traditions to find out how knowledge was passed on from generation to generation. Keynote speakers with experience in the lived tradition of knowledge transmission were invited to share their thoughts, which was very insightful. Mostly in the Indian classical music and dance traditions, we can still find a continuity in the pedagogies of ancient times, therefore by going deeper into these pedagogies, we can find clues about the traditions for other disciplines. The delegates got a deeper understanding from the talks by music and dance gurus who were invited to the conference. The highlight of the event was the Shastraarth or ancient style of discussion and debate by Vedic scholars. It was wonderful to watch two female scholars in the midst of male scholars – all discussing the finer points of grammar in Sanskrit.”

The conference saw excellent discussions after every distinguished lecture and paper presentation. “One important insight I got was that even in order to learn Nritya, one needed to be well-grounded in Sanskrit Vyakarana. To be a good dancer, one has to be able to understand the nuances of the emotion that has been described in a text which is being enacted. Thus, the knowledge of grammar was needed. I found this fascinating!”

As to development across the ages, she says that “Chronology and time periods were not so much the focus of the conference. This is such a huge topic that a separate conference would be needed to discuss the myriad aspects.”

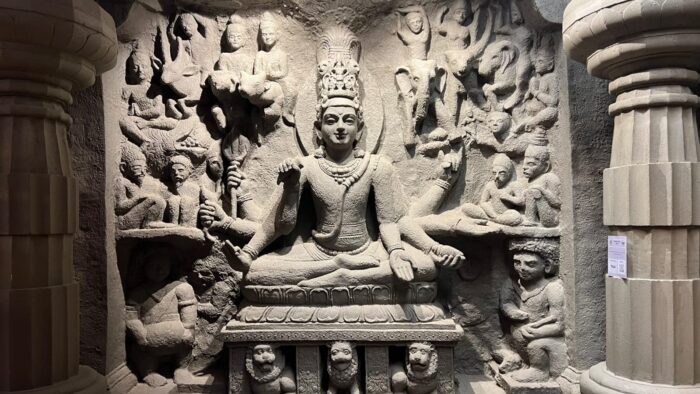

The venue was chosen with great care as Ujjain has always been known for being a hub for inquiry and scholarship. “The contribution of Madhya Pradesh government to our conference was noteworthy. They gave us such an amazingly appropriate venue – the auditorium in the Triveni Museum which must surely rank among the top museums of India. It has mindboggling art and sculptures showcasing the Shaiva, Vaishnava and Shaakta cultures (hence Triveni).”

“When Harikiran Vadlamani ji and I were discussing the venue for this conference, he first suggested Nalanda. But I was in favour of Ujjain because of its extraordinary significance as a centre of education. The zero degree meridian of the precolonial world passed through Ujjain. Also, it is the city of Mahakaaleshwar, one of the 12 Jyotirlingas of India, known to protect Bhaktas from untimely death. Hari ji agreed immediately with me and said we should make it a conference cum teerth yatra.”

Smt Sahana adds “The MP government authorities also reminded us that Ujjain was the site of Guru Sandipani’s Ashram where Bhagwan Krishna along with Balarama and Sudama studied the 64 Kalas (arts). Thus, it has been a centre of learning not just in the common era but from the times before the Mahabharata war.”

In this supremely important place, Dr Ankur Kakkar, Assistant Professor, Center for Indic Studies, Indus University, spoke about the transmission of knowledge in medieval and early modern India, emphasizing the pivotal role of families and jatis. His talk highlights the decentralized nature of Indian education, with various social classes receiving education, especially in disciplines like dance, drama, pottery, and Ayurveda within family settings.

Historiography on Indian education typically focuses on formal institutions, neglecting the significant role of families as custodians of traditional knowledge. Colonial surveys conducted in the 19th century documented the widespread existence of indigenous village schools and colleges, alongside private education in family homes. However, arts and crafts education, primarily transmitted orally and informally within families, were often overlooked.

The hereditary nature of occupations, evident in ancient texts like the Jatakas, underscores the deep-rooted tradition of knowledge transmission within families. Examples include the preservation of Vedic knowledge, Ayurveda, drama, architecture, and pottery through familial training. For instance, Vedic education has been passed down through generations within specific families and Gurukulas. Similarly, the Ashtavaidyans in Kerala and the Chakyar families specialized in Ayurveda and Kutiyattam (Sanskrit drama), respectively, within family-based settings.

Prof Pasumarthy Ramalinga Sastry, Professor Emeritus, Dept of Dance, University of Hyderabad, spoke on Pre Modern Dance Training System at the Kuchipudi Agraharam. Dr Sushruti Santhanam, Carnatic Vocalist and Director Center for Arts, Society and Policy, spoke on the overview of the Abhyasa Gana Pada in Carnatic music.

Dr. Bijoya Baruah, D.Lit. Professor, Dept. of Assamese Mahapurush Srimanta Sankardev University, speaking on Importance Of Folklore: A Unique Ecosystem Of Learning As Traditional Pedagogy Of The Society, said folklore, often misconstrued as mere quaint stories, is a comprehensive cultural phenomenon encompassing traditions, values, language, and more. His paper explores folklore’s historical role as a pedagogical tool, particularly in Indian context, and its potential to augment modern education. It examines how folklore can be integrated into educational frameworks, promoting biodiversity, environmental stewardship, and social well-being.

Folklore comprises diverse genres like material culture, music, prosaic genres, verbal art, belief and religion, foodways, and performing arts forms. Each genre offers unique insights into cultural heritage and societal norms, enriching educational experiences.

The paper advocates for incorporating Folkloristics and applied heritage studies into educational programs to foster well-rounded individuals equipped with 21st-century skills. These fields preserve cultural richness and apply historical wisdom to contemporary challenges.

The paper discusses various pedagogical approaches such as the collaborative, reflective, integrative, and enquiry-based models, highlighting how folklore aligns with these methodologies. Folklore encourages active learning, critical thinking, and cultural sensitivity.

Folklore enriches cognitive and linguistic development through its diverse genres, fostering critical thinking and cultural understanding. It promotes humanistic and moral development by imparting universal values and facilitating reflective discussions. Events like festivals serve as platforms for reinforcing cultural values and promoting community solidarity, bridging the gap between individual learning and communal practice.

Ancient Indian games occupy a unique position in society, blending entertainment with educational content. While some games may have lost their prominence over time, their educational value remains relevant. By recognizing and preserving these games, educators can tap into a rich resource for interdisciplinary learning and holistic education. Incorporating traditional games into modern education systems can bridge the gap between tradition and innovation, offering students valuable insights into history, culture, and human values.

Ms Gowri Ramachandran, Institute for the Advancement of Vedic Mathematics, spoke on Ancient Games and their relevance to Education. This paper explores five traditional Indian games – Pallankuzhi (Mancala), Aadu Puli Aattam (Lambs and Tigers), Paramapadam (Snakes and Ladders), Anchankal (Five Stones), and Chaupar/Pacchisi (Ludo) – to uncover the educational values embedded within them. These games, while primarily recreational, have deeper cultural and educational implications that are worth examining.

The Top of Form

paper titled “‘Foolish student character’ in ‘Paramananda Shishyula Katha’: Unique tale types and pedagogical significance” by Deepa Kiran explores the significance of the folklore series from Telugu literature known as ‘Paramananda Shishyula Katha’. The paper delves into the unique tale type of “foolish students and their teacher” within this series, highlighting its pedagogical implications and relevance.

The author discusses the concept of tradition as knowledge, drawing parallels between oral traditions in Indian and African contexts. They highlight the role of storytelling in transmitting knowledge in Indian texts such as the Jataka tales, Kathasaritasagara, and Panchatantra. The author explores the pedagogical significance of the ‘foolish students and their teacher’ tale type, emphasizing the importance of acknowledging ignorance in the learning process. They draw parallels with Indian texts like the Upanishads, where dialogues between students and teachers are central.

Fenal Shah in his talk: Revitalizing Education Through Ancient Pedagogical Methods: The Role of Storytelling in India’s Educational Heritage, says that rooted in the oral tradition of the Vedas and epitomized in epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata, storytelling has served as a powerful pedagogical tool for transmitting knowledge, instilling values, and fostering character development. This research aims to critically analyze the historical significance of storytelling in ancient Indian education and assess its adaptability to modern educational challenges.

The study will explore traditional pedagogical methods employed in ancient Indian educational institutions, including gurukuls, tapovans, pathshalas, and monasteries.

In the talk, Panchatantra as a Pedagogical Tool in Premodern India: Unveiling the Depths of Ancient Wisdom, Tarini Chandrashekar, says through an in-depth analysis of its socio-cultural-political teachings, one can realize the pedagogical significance of Panchatantra and its relevance in modern education.

The Purvapaksha section challenges the prevailing notion that premodern Indian education was solely focused on religious studies and lacked relevance to modern skills. By examining Western perspectives and scholarly interpretations, she uncovers the underlying bias against ancient Indian knowledge systems.

“Contrary to misconceptions, Panchatantra is not merely a collection of moral stories for children but a sophisticated treatise on worldly wisdom and governance. The Bhoomika section introduces pedagogy as a multifaceted approach encompassing content, methods, and socialization techniques. Paribhasha provides an overview of Panchatantra, highlighting its structure and narrative style. Pramana delves into why Panchatantra is a pedagogical text, emphasizing its role in imparting practical wisdom essential for leadership and governance.”

Adhyaaya explores the narrative teachings of Panchatantra across various domains, including leadership, politics, economics, and critical thinking. Finally, Pashu examines the use of animal motifs in ancient Indian storytelling, revealing deeper symbolic meanings and insights into human behavior.

Swati Dave gives us a glimpse into the fascinating world of Tinnai schools in Tamil Nadu. These local elementary schools, conducted in the verandahs of houses, served as the cornerstone of education for young boys from upper and middle caste groups.

The core values of Tinnai schools revolved around preparing children for adulthood by imparting practical skills in literacy and numeracy within the context of their local society. Tinnai schools operated on a flexible fee structure, with families contributing to the teacher’s livelihood through cash, kind, or even labor on agricultural land.

Unlike modern schools, Tinnai schools lacked formal governing bodies, with community input shaping the curriculum and teaching methods. Class structure was based on students’ understanding rather than age, with senior students assisting in instruction under the teacher’s guidance. The curriculum was tailored to meet local needs, combining language and numeracy skills with moral lessons and practical knowledge relevant to agriculture and commerce. This personalized approach fostered a deep understanding of subjects and promoted holistic learning.

Smt Anita Korde spoke about the Sompura community, hailing from Prabhas Patan (also known as Somnath Patan) in western India, renowned for its expertise in sculpture and architecture. With a lineage dating back to antiquity, they have left an indelible mark on Indian temple architecture, particularly in the Nagara style. Their legacy is evident in the construction of numerous temples and structures across the country, including iconic landmarks like the Akshardham Temple in Gandhinagar and the Somnath Temple in Gujarat.

The Sompura community’s mastery of temple architecture is deeply rooted in the ancient principles of Vastu Shastra, a science that harmonizes spiritual beliefs with architectural design. This blend of spirituality and engineering prowess ensures that their creations not only inspire awe but also stand the test of time.

Despite facing challenges brought about by societal changes and modernization, the Sompura community remains steadfast in preserving and revitalizing “living” temples, passing down their knowledge from one generation to the next. Their commitment to upholding traditional practices while embracing technological advances reflects their adaptability and resilience.

Lessons in Servant Leadership – Professional Training, Cross-Disciplinary Learning, and Traditional Continuity in Śaivāgama Pāṭaśālās by Dr. Deepa Duraiswamy, T. S. Bhuvaneshi Shanmugam and T. S. Sambhavi Shanmugam say for millennia, the guardians of our temple ecosystem have been the Ādiśaiva ācāryas, who base their teachings on the Śaivāgamas. Historical inscriptions attest to the multifaceted roles of these ācāryas, serving as advisors to royalty, personal counselors, temple priests, educators, and spiritual guides. They fulfilled diverse roles, from resolving personal dilemmas to providing medical, psychological, and philosophical support.

Central to the development of these ācāryas was the rigorous training provided in pāṭaśālās, traditional educational institutions dedicated to the study of the Śaivāgamas. This paper delves into the historical significance of these pāṭaśālās and extracts valuable insights for modern pedagogy.

In the study of the “Indic Education System as Reflected in the Caitanya Caritāmṛta: A Hagiography of Śrī Kṛṣṇa Caitanya”, Snehā Nagarkar, Doctoral Research Scholar, says Śrī Kṛṣṇa Caitanya (1486-1533 CE), the Bengali saint, catalyzed a revolutionary shift in the Medieval Bhakti Movement across India. The principal hagiography of Caitanya, the Caitanya Caritāmṛta, authored by Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja in Vṛndāvana during the early 17th century CE, delineates his life in three segments: the Ādi, Madhya, and Antya Līlās, employing verses in both Sanskrit and Bengali. This paper delves into the portrayal of Caitanya’s life within the Caitanya Caritāmṛta to glean insights into the Indic education system prevalent during his era. By analyzing this seminal text, we aim to elucidate the pedagogical methods, philosophical underpinnings, and cultural nuances embedded within the Guru-Śiṣya Paramparā, shedding light on the enduring tradition of Bhakti education.

Sadas: The Conference had a Vaakyaartha/Shaastraartha Sadas featuring Nyaya, Vedanta and Vyakarna Scholars. It was organized, to demonstrate how, in traditional shaastra learning, paddhati debating method is used part of teaching and learning and is followed as a method of continuing education to hone the shaastric skills and to cultivate creativity throughout life. This was organized under the leadership of two senior shaastra scholars Dr Sandeep Kumar Sharma , a local Ujjain scholar running two shaastra paratha shaalas and Dr Jammalamadaka Srinivasa Sharma of Kameswari Peetham, Hyderabad.

The Sadas was presided over by Prof. Sripada Subrahmanyam garu a polymath senior shaastra scholar. A rare aspect that was included in this sadas was that two women scholars also shared stage with the men scholars participated in the propsition and its defence through the shaastriya procedure.

Dr. Siva Kumari Katuri, Vyakarana Scholar made and defended her proposition on “Dhātusambandhe Pratyayā: Sūtravyākhyānam.” Kum. Simran Thakur, Vyakarana Scholar made and defended her proposition on “Laghuśabdenduśekhare Rapratyāhāravichāraḥ.” Dr. Srinivas Jammalamadaka, Nyaya Scholar made and defended his proposition on “Vāda-Jalpa-Vitaṇḍā-Nirūpaṇaṃ”. Dr. Sandeep Kumar Sharma, Nyaya Scholar, made and defended his proposition on “Īśvarānumānaṃ.” Sri Uddhav Pouranik Nyaya Scholar made and defended his proposition on “Siddhāntavyāptivichāraḥ.” Sri Vinayaka Pouranik, Nyaya Scholar made and defended his proposition on “Dinakaryām Yogyatāgranthaḥ. “Sri Sartha Shukla, Nyaya Scholar made and defended his proposition on “Dinakaryām Pṛthivīgranthaḥ.” Sri VIkas Sharma, Nyaya Scholar made and defended his proposition on “DinakaryāmVākyalakṣṇānirāsaḥ.”

Sri Sachin Dwivedi, Vedanta Scholar made and defended his proposition on “Advaitasiddhau Tṛtīiamithyātvanirūpaṇaṃ.” Sri Chinmay Munje, Nyaya Scholar made and defended his proposition on “Muktāvalyām Samāsavichāraḥ.”

Dr Mala Kapadia talk on “Unveiling the Pedagogical Insights of Atharva Veda: A Journey towards Self-Mastery and Higher Intelligence” shows the profound educational insights embedded within the Atharva Veda. The paper explores the foundational principles of education outlined in the Atharva Veda and elucidates their relevance in contemporary pedagogical practices.

The Atharva Veda emphasizes the significance of self-knowledge and its transmission to learners as essential qualities of a competent teacher. Through a Nature-centric approach to learning, students are encouraged to embark on a journey of self-mastery and self-transcendence, realizing the interconnectedness of the Macrocosm and Microcosm.

Furthermore, the Atharva Veda delineates the purpose and outcomes of education, emphasizing the creation of Medha or Higher Intelligence, the integration of Head and Heart, and the pursuit of Dharma. The concept of Medha as Right Temper is contrasted with the Western Scientific Temper, offering insights into a holistic approach to education that integrates Swabhav (inherent nature) and Swadharma (individual duty).

Dr. Lalitha Sarma R (Project Research Scientist, CISTS, IIT Bombay), says the Śikṣāvallī of the Taittirīya Upaniṣad serves as a reservoir of educational philosophy and pedagogical insights, encapsulating the essence of an educational system that transcends mere knowledge dissemination. This paper delves into the profound teachings of the Upaniṣad, shedding light on its multifaceted approach to education.

The Śānti Pāṭha within the Taittirīya Upaniṣad underscores the importance of creating a conducive learning environment, emphasizing the need to cultivate an atmosphere that fosters intellectual growth. The systematic recapitulation method employed in the Upaniṣad facilitates seamless progression through the learning journey, laying a strong foundation for the continuity of knowledge says Dr Lalitha Sarma.

Furthermore, the Upaniṣad places significant emphasis on phonetics and language proficiency, recognizing oral knowledge transmission and linguistic skills as fundamental pillars of higher education. The concept of Upāsanā, extensively explored in the Śikṣāvallī, not only serves as a spiritual practice but also emerges as a powerful pedagogical tool, illustrating the holistic nature of education.

Dr. Jayashree Aanand Gajjam in her talk Exploring the Upaniṣadic Way of Pedagogy: Insights from the Guru-Śiṣya Paraṁparā Embedded in the Chāndogya Upaniṣad, presents a treasure trove of rich and comprehensive dialogues between a revered teacher (Guru) and a devoted disciple (Śiṣya). Through a meticulous content analysis of twelve selected conversations within the Chāndogya Upaniṣad, this paper extracts key insights on teaching and learning methodologies, drawing parallels with foundational concepts in modern pedagogy, andragogy, and virtue epistemology from Western philosophy.

Smt Nritya Jagannathan explores the continuity of classical yoga pedagogy as exemplified in the teaching methodology of T Krishnamacharya and its relevance in modern yoga practice. Drawing on Desikachar’s transformative journey and Krishnamacharya’s multifaceted approach to teaching, the paper highlights the importance of sādhanā in yoga education. It critiques the modern trend of reducing yoga to mere physical exercise and advocates for a return to the holistic pedagogical principles of classical yoga, rooted in Vedic lore.

Ancient knowledge systems were upheld by well-defined research methods, with Tantrayukti playing a pivotal role in interpreting science across various disciplines says Dr Sarita Seshagiri. Influential theoreticians and practitioners in fields such as Statecraft, Economics, Medicine, Philosophy, and Grammar utilized Tantrayukti’s methodological devices to structure their treatises, resulting in enduring expositions that withstand the test of time. This paper explores the potential for contemporary qualitative research in social studies to enhance its content and presentation by borrowing methodological tools from Tantrayukti.

Drawing from the author’s experience in research projects and academic paper reviews, the paper discusses how current qualitative research often faces challenges due to poorly conceived research plans and ineffective presentation of study outcomes. By integrating Tantrayukti’s principles, qualitative research can address core research problems rigorously during field immersions and improve research ethics. Additionally, Tantrayukti offers insights into presenting study outcomes more cogently, thereby enhancing the impact and accessibility of research findings.

The paper provides an introduction to the importance of qualitative methods in data gathering, followed by an overview of Tantrayukti’s principles. It then delves into specific hurdles encountered in qualitative field-data collection and analysis, as well as issues with the publication of such studies. Relevant Tantrayukti devices are highlighted as solutions to these challenges, offering researchers a pathway to strengthen their work while adhering to modern methodological requirements.

The Indic educational heritage is rich and varied, encompassing diverse traditions and methodologies that have evolved over millennia. In her paper, Uma Maheswari Shankar, Principal and Head of the Department of Philosophy at SIES College of Arts, Science & Commerce, explores the pedagogical tools and practices that have shaped education in India from ancient times to the present day.

Shankar begins by highlighting the traditional educational institutions of ancient India, such as Gurukulas, Pathshalas, Mathas, Agraharas, Viharas, and Mahaviharas, which attracted scholars from across the globe. These institutions were not only centers of learning but also hubs of intellectual debates and discussions. Shankar emphasizes the importance of deliberation, discussion, and debate in both general discourse and academic pursuits, citing Swami Vivekananda’s assertion that “education is life itself.”

The paper traces the evolution of Indian education through various historical periods, noting the influence of different civilizations and ideologies. Shankar discusses the impact of Aryan, Buddhist, and Islamic influences on Indian education, highlighting the democratic nature of learning in historic times, where individuals from diverse backgrounds came together as fellow disciples under a common tutor.

Furthermore, Shankar examines the role of oral transmission and written texts in preserving and spreading knowledge, as well as debates surrounding the effectiveness of traditional Gurukul systems versus formal schools. She categorizes educational institutions into three broad types: home-based schools, debate circles or parishads, and conferences arranged at different places. Each of these institutions served different purposes and catered to various types of learners.

The paper also delves into debates surrounding the role of teachers in ancient education, the emphasis on philosophical versus practical knowledge, and the teaching methods and curriculum used in ancient educational systems. Shankar acknowledges the diversity of opinions and perspectives within the realm of ancient education, emphasizing the need for critical examination and scholarly discourse.

The axiology of the Vedic era, which emphasized universal eternal values such as truth, goodness, and beauty, is highlighted as integral to ancient Indian education. The interconnectedness of personal and social values underscored the holistic nature of education, which aimed at the harmonious development of physical, mental, and spiritual aspects of human life.

Dr Kamala Srinivas discusses the classification of education based on Varnashramadharma and Purusharthas, which determined one’s pursuit in life and aimed at the overall progress of humanity. The enduring relevance of ancient Indian education is emphasized, with Mr. F.E. Keay noting its resilience and enduring impact on intellectual life worldwide.

Furthermore, the introduction introduces the concept of critical thinking pedagogy in the Vedas and Upanishads, highlighting the three-step process of Sravana, Manana, and Nididhyasana. The Upanishads are presented as exemplars of critical thinking pedagogy, wherein the Guru engages in experiential teaching-learning methods through discussion and debate with the Shishya.

Finally, she underscores the need to reconceive critical thinking as both reflective and reflexive in the present context, emphasizing the importance of deep thought and self-awareness in education. By cultivating both reflective and reflexive thinking, students can engage more deeply with their studies and develop a greater understanding of themselves and the world around them.

Dr Shailendra Kumar Sharma gave the valedictory address. Acharya Muneet Dhiman, Kulapati Vidyakshetra Gurukulam, spoke on the Kosha based education at Vidyakshetra in Bengaluru which in essence summarises the Bharatiya method. The Indian education system has historically been built upon the principles of Panchkoshatmika Vikas, ensuring holistic development of the child across various dimensions. These principles focus on nurturing different aspects of a child’s being, as outlined below:

Annamaya Kosha: This focuses on building a healthy and fit body through good sleep, play, and eating habits. It emphasizes the importance of establishing healthy rhythms in life, both at school and at home. Pranamaya Kosha: It aims to strengthen the inner systems of the body and improve vital energy through practices like yoga, martial arts, sports, and disciplined habits. Discipline in various aspects of life, such as eating, speaking, understanding values, and time management, is emphasized. Manomaya Kosha: This aspect concentrates on nurturing the mind, emphasizing the development of qualities like focus, determination, patience, and self-confidence. It involves engaging with a carefully designed curriculum and pedagogy that fosters both academic and personal growth. Vigyanmaya Kosha: Here, the emphasis is on experiential learning and developing wisdom (viveka) through engagement with various subjects, nature, and community. It encourages students to understand their interdependence with family, society, environment, and spirituality. Anandmaya Kosha: This focuses on spiritual development and encourages students to explore the deeper aspects of life, connecting actions and thoughts with the supreme consciousness. It emphasizes the importance of understanding and experiencing the interconnectedness of all aspects of existence.

Furthermore, the education system aims to reconnect individuals with their families, society, environment, and spiritual pursuits. It seeks to create a sustainable, interdependent community called “Vidyagram,” where individuals can live in harmony with nature and each other. This community model emphasizes self-sufficiency, craftsmanship, and inclusivity, aiming to provide a replicable Dharmic model of sustainability.

In essence, the holistic education system aims to foster not only academic excellence but also physical well-being, mental resilience, emotional intelligence, spiritual growth, and a sense of interconnectedness with the world around us. It strives to prepare individuals to make sustainable choices, contribute positively to society, and lead fulfilling lives aligned with timeless values and principles.